Ultimate Victory

Alappuzha, Kerala, 2002

I wrote this piece more than two decades ago, in the long shadow cast by September 11. I was young, far from home, and watching the world rearrange itself around fear, power, and consequence. Reading it now, as wars multiply and images of devastation once again flood our screens—from Gaza to Iran to Sudan—it feels less like a memory and more like a mirror.

EVERYONE REMEMBERS where they were when the Twin Towers fell. It was one of those once-in-a-lifetime moments that made time stand still. I was in Chennai, South India, in the one-room house of my mother’s younger sister, watching the iconic towers smoke like matchsticks before collapsing a hundred stories to ground zero.

No one yet understood how completely this singular event would redraw the world—increased airport surveillance, endless wars in the Middle East, a new vocabulary of fear. It felt as though we had all been living in a collective naivety that evaporated overnight, replaced by suicide bombers, weapons of mass destruction, and suspicion lingering in airport lines. On a Tamil news station, I watched the footage loop again and again, uncertain at first of what I was even seeing, but knowing instinctively that it was enormous. My aunt tried to change the channel to the high-pitched shrill of film songs, but I couldn’t look away. Over and over, a Boeing 747 tore into the final tower, until American invincibility was reduced to rubble.

A FEW MONTHS LATER, my Australian boyfriend and I found ourselves in Alappuzha, a small Keralan town known as the “Venice of the East,” famous for its peaceful backwaters and dense green canals. It seemed an unlikely place for what awaited us: a massive anti-war demonstration. Reports estimated nearly 25,000 people would march under the blazing sun, united by a single intention—to resist the looming American invasion of Iraq.

In just a few days there, I had witnessed Hindu temples layered with intricate carvings, images of Jesus taped to shop walls, and the call to prayer spilling from mosques. The coexistence felt effortless. Seeing that same diversity move as one body through the streets felt quietly radical.

Soon I was caught in the swarm, swept forward by chanting and drums. Hand-painted signs bobbed above us: No War. Impeach Bush. Children from local schools were ushered into place first, and paper hats and banners were distributed to the rest of the waiting crowd. Speeches echoed across the grounds, music drifting in from nearby hotels—none of it intelligible to me, but all of it charged.

I noticed I was one of the only foreigners there. A young Indian man approached, offering polite questions, but my attention kept drifting to a man beside me in a homemade wheelchair. He was cross-eyed, his feet severely misshapen, his arms flung skyward as he shouted with ferocity. His urgency eclipsed his physical form. I wondered briefly whether this was a peace rally or an anti-American protest.

That uncertainty deepened when I noticed a large paper mosque ahead, a plastic missile mounted above it, pointed at the sky.

The march began. Men flashed me thumbs-up. Journalists clustered around, snapping photos. I had the fleeting, familiar sensation of being famous, of being mistaken for someone important simply because I was not from here. We moved toward a sports field where performances and speeches would close the day. The heat was punishing, but the crowd's energy carried me forward.

Women in vivid saris walked ahead of me, their long hair gleaming down their backs. Men wore traditional white cotton robes. Children toddled alongside their parents in No War t-shirts. The gravity of Iraq felt deeply personal here—perhaps because so many in the crowd shared a faith already under global suspicion. Eyes met mine again and again. I realized nearly as many people were watching as marching. I laughed quietly at how obvious I must have looked.

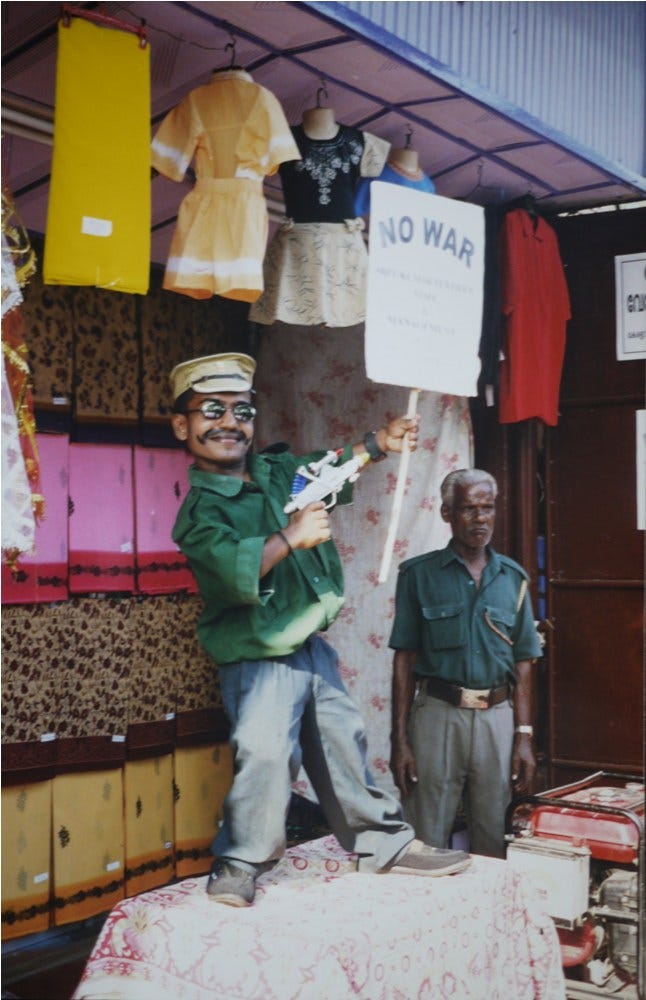

Along the route, protest became spectacle. A shopkeeper displayed two mannequins: one dressed as an American soldier, the other in a blood-stained shirt, an Iraqi civilian. A little person stood on a platform holding a toy gun, smiling as I passed. The man in the wheelchair rolled by again, still shouting. Songs rose and fell through the heat, broken occasionally by men angrily listing the names of countries America had already scarred. Yet beneath it all was sincerity—a collective belief that peace was still worth protecting. People smiled at me with something like gratitude, as if my presence itself affirmed their cause.

At the sports field, hundreds were already seated before a stage. A small tent sheltered local celebrities and officials. Photographers crowded forward. Speeches began, followed by awards, then music and dance—intricate rhythms and ancient movements filling the dusk.

The most arresting performance came last.

A group of men reenacted the bombing of the Twin Towers. They danced to erratic drumming, then assembled into a human pyramid. A handmade plane crashed into them. A poster of the real image dropped from above as they fell to the ground. The crowd laughed and cheered—not out of cruelty, but catharsis.

Then two doves were released.

One flew gracefully toward the setting sun. The other fluttered awkwardly and landed behind the stage.

Watching them, I understood what the entire day had been circling. Even the universal symbol of peace hesitated. Even peace itself did not always know which direction to take. The division was unavoidable—in nature, in people, in nations.

Victory, I realized, was never going to be found on a battlefield, nor even in preventing a war outright. It had already happened, briefly and imperfectly, in the streets of a small Keralan town—in the act of gathering, of standing together, of choosing union over silence.

That, at least, had already been won.

MORE LIKE THIS