In 2015, Caitlin Press published my short story, “The Other Side of Freedom,” in This Place A Stranger, an anthology of Canadian women writing about their experiences of travelling alone. In this story, I am in Port Sudan, retracing the delicate steps of a love once shared with a Darfurian refugee in Tel Aviv, confronting the chasm between freedom and displacement, the injustice of exile, and my own complicated privilege. I share this story with you today, in honour of World Refugee Day, which took place June 20th.

With a convincing look on her face, the woman perched at the front door insists that I sit inside and smoke, protecting me from the interested eyes of the men gathered in small vulturous groups on the street corners.

The refreshing sea breeze and the spectacle of the busy local street are far more compelling than the double lines of dirty plastic chairs where I am told to sit. In one corner a desk is stacked with unused pipes—spare hoses hanging in a precarious jumble atop an unused fan. She is right. A woman smoking shisha, and a hawaja (foreigner) at that, attracts too much unwanted attention.

This is not cosmopolitan Cairo after all; I am in Sudan.

I bring a book with me—partly because I want to read it but mostly because it’s a strategy to occupy my eyes from meeting the astonished gaze of other customers. Light from a tiny window near the ceiling glints off the bald head of the man preparing my pipe. His face has a noble quality to it and he seems to take his work very seriously, though I cannot discern his opinion about a woman preparing to engage in a decidedly masculine activity. I sense he is curious about my reasons for being in this port city since it rarely sees casual travellers pass through its seafoam-scented streets. Nonetheless, he does as any self-respecting man would do in public—he makes no inquiries that give his interest visibility.

Before I can change my mind he abruptly places a water pipe at my feet, wraps the mouthpiece in aluminum foil and hands me the hose. I have ample years of shisha smoking under my belt from the Mediterranean joints I frequent back home, but I am rarely the one who gets a pipe started. The sheer force of inhalation needed to get it going is enormous for my untrained lungs and always results in a dizzy spell. This time I must go it alone, and such a simple task feels like an evaluation of my mastery in front of this curious crowd. I calmly hold the hose in my left hand and expertly shift the coals with my right, my newly purchased brass bangles clanging together while I attempt to appear as cool as possible. The onlookers are throwing sideways glances my way and at each other as they survey my next movement. With puckered lips I suck the foil-covered hose, and the nerve-calming sound of water gurgles as the tobacco cools and rises to my lips with sweet familiarity. Exhaling a respectable volume of smoke, I keep my eyes fixed on the page I am using as my decoy, aware that every man here is watching me or pretending not to. I too am pretending not to watch them watch me.

I feel like retching as my body finds the balance between the heady shisha toofah and the sickly-sweet coffee. Didn’t I say “zucar shuaya?” Apparently this is what is meant by less sugar. I’ll have to try “no sugar” next time and see if that procures my desired taste. Men of all different dress and social stature are pouring in. I feel like I am in the equivalent of a Cuban cigar lounge with far plainer trimmings. Some have typical African features and others look more Arab; some dress in traditional jalabiya and others in plain Western clothes; most of them play with their mobile phones. Perhaps they too require a decoy of some kind to hide their embarrassment. At this point the entire line of chairs across from me is filled with intrigued patrons while I sit alone on the other side, save for a single man in the corner who hasn’t looked up from his pipe since I arrived. He must legitimately be here for the shisha and orders a second pipe. I out-smoke all of them but him.

Nausea from the tobacco fills me. My head is spinning, my attention caught by a television set in the corner spewing unfamiliar rhythms of rapid, lively beats, quite unlike the gentle, sophisticated croons of Sudanese music. The screen is filled with dizzying images of women thrusting their hips to meet their clapping hands and scenes of couples in verdant hills frenzied with passion. This most certainly wasn’t the country I was in. The Sudanese are a mild-mannered bunch who display their enthusiasm by snapping their fingers and shrugging their shoulders. Hips, cleavage and even ankles are a no-go zone. For the past week I have done everything in my power to deny that I have a figure, preferring to respectfully shroud it in head-to-toe jalabiya. It dawns on me that this shisha bar may in fact be a hotbed of sinful activity, from smoking to ogling the half-naked girls in Ethiopian music videos. To set the record straight, the men of Sudan have been very decent in my presence—except for that one who got away with a firm hand on my backside while posing for a photo! Still, the complete lack of ladies on the streets has been unsettling and reminds me that I am out of my element here. I cannot help but reflect on the vast cultural and gender differences I’m encountering and I’m sure the locals are also whispering about how we female hawaja are able to roam as we please. I begin to wonder if I am as crazy as I seem.

Only I know that my heart is forever intertwined with this land.

Half a year earlier I began my trip in Israel. It was during the afternoon of a bomb scare in the Tel Aviv Central Bus Station that I met a black man with a bicycle and inquired about an escape route. Adam told me he was from Darfur and taught English to other refugees. I had heard that there were many displaced persons from various East African countries seeking asylum here, and this was confirmed by the volume of homeless Africans who lived in Levinsky Park just across the street. My penchant for unusual experiences prompted me to boldly ask if I would be able to visit his class. He seemed as enthusiastic as I to introduce a real native speaker to his students. That evening, in a dilapidated courtyard obscured by laundry drying on a line, I was introduced to a handful of refugees from Darfur who had escaped genocide only to find themselves in a windowless, fluorescent-lit room in Tel Aviv, where Adam also slept.

There I bravely stood in front of twenty young men who were utterly stunned at the sight of me. I introduced myself and told them about the impressive journey I was about to begin. In a week’s time I would start walking the Israel National Trail with an organization promoting peace. We would begin in Eilat at the southernmost tip and walk until we reached Jerusalem. It would be a staggering six weeks filled with campfire songs, exciting new friendships and astonishing views. I encouraged each student to introduce themselves despite their apparent shyness. Every now and again they would break out in nervous laughter and talk amongst themselves in indistinct languages. Each one was respectful and cautious when speaking, and they flashed the whitest sets of teeth I had ever seen. I looked at each of their faces and wondered what stories they hid. Had they seen their parents murdered before them or lost their own children before fleeing? And how did they come this far? I learned that all of them had crossed the desert by foot, lived in intolerable conditions in Egypt and then took the risk to cross the Sinai to come to Israel. Unfortunately, they had not found the welcome they had hoped but were not allowed to leave. No one else wanted them. Suddenly my incredible trip began to feel like a mockery of the punishing journey they had made for peace and security. At the end of the class, each man personally thanked me with a handshake and begged me to return. When the last student had departed, I sat in a warm chair in the first row and burst into tears. Adam sat beside me and put his hand on my shoulder. “I know,” he said, looking at the floor. “I know.”

For the following four months these people would become my family and my world. I learned of their plight, their resilience in very uncertain conditions, and I unexpectedly fell into a very uncertain love.

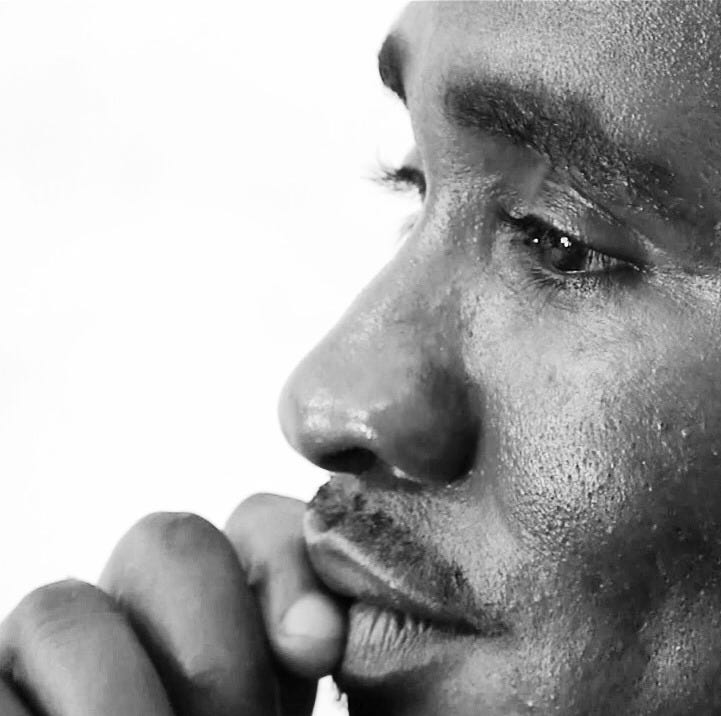

His name was Taher and he had eyes like black moons filled with a sorrow that was too overwhelming to comprehend. I sensed his feelings for me growing over the months, but we had never been alone. When he finally invited me to his house, I felt like a crook accepting. I had yet to tell the class that I had bought a ticket to Istanbul departing a mere two weeks later. How could I consummate our affections knowing that I would leave him? Something pressed me onwards. Taher possessed a rare humility, uncanny sparkle and innocence in spite of the tragedy he had endured. A naive part of me believed that by loving this man I would be able to cleanse him of all his suffering. I would act like a defibrillator, jump-starting his shattered heart and bringing it back to a life where the slate was wiped clean. I would create a space where he could release all that he had carried through the merciless deserts between the home of his heart and the place he sought refuge. It was a selfish saviour complex complicated by real feelings. The world I lived in was one of freedom, independence and possibility, and I knew his was of survival, anxiety and uncertainty. In a matter of time I would be on the road again, wandering wherever I pleased for nothing but pleasure. And him? He would continue to live in a country that did not validate his search for asylum; he’d participate in large-scale protests and finally be stripped of any meagre existence he had managed to cultivate by being placed in a detention centre with other refugees. This was the only sliver of time in which our two worlds could interlace. Perhaps it was this sense of urgency that camouflaged the inevitable pain awaiting. We surrendered to our fate.

Until our final night I had never seen Taher cry. He had lost much in his life, and even this he could not keep. Like the tide drawing inwards, collecting in fervour, the force of his tears struck like a Tsunami whose origin was the bowels of the earth. His pain kindled mine and soon we were both shedding a tidal wave of helpless tears. Until now I had not realized just how immature my belief was that I could continue unaffected by this encounter. Taher had offered me his whole world in a grain of desert sand and it was the sincerity with which he gave this humble gift that crumbled my soul. His circumstances afforded him a deep gratitude for simplicity and I envied how uncomplicated his heart was. He assured me that even if he married someone else, he would build a room in his home in Darfur just for my visits. I didn’t dare protest such a harmless dream even if we both knew the uncertainty of life. I imagined us aged and wrinkled like two characters in a novel meeting years after our brief, youthful love affair. I saw him wearing a long tunic, standing tall and proud in his village with his naked toes sunken in the sand. In his smile I’d see the young man I had loved and everything would be in its perfect place. However, in this moment everything felt sickly wrong. The world was unreasonable if a good-natured, peace-loving gentleman couldn’t even dream about the bright future he deserved.

As my taxi began its journey away from him, I turned to wave but couldn’t make out his face. The contours of his black silhouette bled into the expanse of an equally black sky. His clean and pressed white shirt remained the last visible speck of him as we hurtled through the gritty streets of south Tel Aviv.

Now here I sit smoking a water pipe in the very country that robbed Taher of everything, this act being my own silent protest of the inequity of this world. I wrestle with a nagging guilt. I have been travelling for leisure as long as he has been a refugee. I’ve prized my liberty and the vast experience it has granted me, yet I’m imprisoned by the shame I feel for not using this privilege to emancipate others from the injustice they suffer. I’m burdened by the price of my indulgence, and any exhilaration I felt is deflated by the despair of his exile. I have to get out of here.

It is impossible to enjoy my freedom when someone I love is a prisoner.

Without regarding the aroused attention of all the other smokers when I stand, I raise my eyebrows to the bald guy in a gesture that signals I am ready to pay. I make a move to the entrance, inhaling a breath of air perfumed with salt and exhaust fumes. So this is what it feels like to be different, to be pointed out and measured. It is a paradox to wish for anonymity and invisibility in this country when Taher only wishes to be recognized for who he is anywhere.

With the sweet flavour of apple tobacco lingering on my lips, I hear the haunting echo of the muezzin calling all pious Muslims to their carpets. Taher’s perseverance has taught me that faith is the strongest pillar of the self, and so I close my eyes and let my prayer be like two giant arms embracing him and welcoming him home. I step out into the street; the sun floods my unadjusted eyes. I hear the acceleration of a rickshaw behind me, and laughter in the distance, as I keep my gaze firmly fixed on my destination and my head held high. With rattled nerves I sail into the shabby hotel lobby on the wings of my gentle intoxication, turning back to inspect the scene once I am safely on the other side. From this distance, the dingy cement box I spent the last hour in looks pretty average—hardly the lair from which I could change the world. Rather, it is the world that is changing me and this is where it all starts.

Sacred Assignment: The Small Revolutions of Connection

People become refugees not because they are lost, but because they are unwanted. They flee persecution, stripped of their rights, dehumanized, and threatened. Around the world, many nations still operate from a supremacist belief—the idea that some have more right than others to belong, to claim land, to call a place home. These beliefs don’t only live in governments. They live in us.

It is up to each of us to do our small part to dismantle supremacy—not just in systems, but in our own minds. In the ways we assume we are right. In the ways we see others as less than. In the quiet calculations where our comfort outweighs someone else’s humanity.

Supremacy is insidious. It is woven into the fabric of many toxic, human-made systems—but it can begin to unravel when we meet each other with dignity.

Your sacred assignment this week is simple, but radical: challenge a silent judgment.

Instead of shrinking away or looking past someone you’d usually avoid, engage.

Say hello in the supermarket aisle. Smile at the weary cashier. Offer eye contact to the person everyone else ignores.

Make a single human connection with someone you might otherwise pass by.

Let this be a small act of remembrance—for those who have been cast out, and for the better world we are slowly weaving back together.