In 1981, my mother arrived to the flat, windy prairies of Alberta from the tropical, sunbaked earth of South India.

She had married my Scottish father in her hometown not long before, following a short courtship by Western standards. There is a yellowing photograph of her pregnant, standing in the snow in a long, white, woollen coat, ears wrapped in a scarf, with an expression I can’t translate. She told me that the first time she ever saw snow she asked my dad, “What’s that white stuff on the ground?” On the way to the hospital where I would be born the following day, my father asked her to climb out of the red Volvo hatchback into the blinding winter whiteness of her new world and pose for a photo. I can only imagine what she must’ve been thinking.

As a child, my notion of the Indian subcontinent was first formed by the high-pitched shrill of old Bollywood movie songs blaring from my dad’s cassette player and my mother’s loud phone voice as she tried to communicate with various family members on the other side of the world. She received letters in mysterious squiggles that I couldn’t decipher and there was always some distant relative we had to greet on long distance calls.

When I was growing up it wasn't cool to have a mom from India. We were still deep in the clutches of a conservative, settler mentality in Alberta. Even the Greek family who owned the pizza place across the street from my elementary school seemed to be from another planet. When my mom picked me up from school, my face would grow hot with embarrassment at seeing her brown head behind the steering wheel of our station wagon. I hated the way she'd crack chicken bones between her molars and noisily suck the marrow out. Or how she'd sit straddling the kitchen sink, pulling the skin of a mango between her teeth. I despised the whistle of the pressure cooker, the dinner parties, and the secrets we had to keep to avoid the disruptive force of an ‘evil eye’ gazing upon us in envy.

My mother has lived between two worlds, two hearts, two homes for as long as I have known her. In Canada, she created a family, learned to drive, cut off her long hair and traded her sari in for jeans. She became a single, independent woman for the first time in her life after my parent’s divorce, facing a stigma that is often the death of one’s reputation where she comes from. And yet, she has never left India behind. She spends hours a day on phone calls to sisters and cousins, keeps up with the latest movies, and still battles between spending time in the banyan-shaded streets of her childhood or cooking her infamous Sunday curry dinner for my brother in Calgary.

Her profound nostalgia for her motherland and its influence on my life has instilled in me a sense of rootlessness, as if I, too, have grown up between the two worlds she fights between, forever a visitor in both. Despite all the ways I believed I had rejected all of this in my youth, my solo trips to India would reveal just how deeply her culture's nuances had grafted themselves onto my identity.

Madras, as it was known when my mother grew up there, is a throbbing entanglement of sweat-slicked bodies frying beneath the relentless sun.

The streets are perfumed with the fragrance of jasmine garlands hanging from women’s oiled hair, while filigreed gold jewellery sparkles against dark skin. People’s gazes are as intense as the heat. I was visiting my relatives on Alikhan Street, in the neighbourhood where my mother grew up. Everything felt both foreign and strangely familiar: my auntie’s humid kitchen, where I could smell the same curries my mother makes back home and where I saw a small shrine to the Hindu gods adorned with various photos of our deceased ancestors. I heard the familiar melody of Tamil in my ears, and recognized the movie songs blaring from countless tv sets like an orchestra in the densely populated block.

I sat on the floor on a rolled-out bamboo mat with my soft-skinned potima—grandma—who called out my mother’s name, “Geetha.” Using the edge of her sari she wiped tears from beneath the thick bifocals that magnified her eyes like black saucers. Her cry was a primal, instinctual call for her daughter to return to her arms, to the home where she belongs.

She sat against a wall, surrounded by a pool of cloth, only getting up to use the bathroom. Several years earlier, she broke her hip from a fall on the stairs, and rather than have it fixed due to financial constraints, she let it heal naturally. This had left her unable to walk normally; she could only shuffle her feet sideways, painfully slowly, which often resulted in her accidentally urinating on the hallway floor just a few steps from the bathroom.

Despite the injustice of poverty, my grandmother was beautiful, and made from the pure light of a mother’s love. I took her bony hands in mine and swallowed the lump in my throat as she wept. Her giant pupils stared at me through her foggy glasses as a smile softened her face.

It struck me that the pain my grandmother felt for her daughter’s absence, the girl she carried, loved, and let fly free is the same heartache my mother feels when I am thousands of miles from home. In that moment, I wished more than anything that my mother was there with me, to bridge the language divide, to crumple into the tear-soaked bosom of my grandma and to put a sense of rightness back to her and my world. By witnessing my grandma’s grief for her daughter’s absence, I felt my mother’s pain with renewed compassion.

Although I couldn’t think of what to do to alleviate my grandmother’s sorrow, I hoped that my mere presence carried some significance. Afterall, I was a part of my mother searching for answers in India, a restless spirit trying to reclaim what was lost. Without this understanding of her roots, I hadn’t truly understood who my mother was. I needed this window into her motherland, to see how it made her who she is and how much of all that was in me too.

After spending many years in India on my own, I realized my childhood denial of my mother’s culture was ultimately a denial of my self.

Finally, I wanted to wear jewelled bindis between my eyes, bask in the smoke of Nag Champa incense, and bob my head from side to side like a Thanjavur paper-mache doll. I felt a pang of envy when I met other travellers who had no shared heritage with the country but had adopted many of the customs I’d avoided most of my life.

Indians always regarded me as a foreigner until they heard my name and frowned with curiosity. They couldn’t imagine that I, too, grew up with the flicker of the oil lamp lit on my mother’s shrine, that my house smelled like turmeric and fried cumin, that I went to Tamil school on the weekends. Instead, I looked like all the other tourists in the country—a seeker. And honestly, I was seeking something on the smoothed stone floor of temples, by eating rice with my hand on a banana leaf like my ancestors did, and listening to the clicking tongues of my aunties as they gossiped and laughed and played cards on the rooftop until midnight. I was looking for where I belong. Although, I did find a place where my soul felt at peace, I couldn’t deny that I belonged just as much to the ways conservative Indian values made me feel ashamed of my wildness, how they kept me small, and from speaking and living my truth.

It has been the quest of my lifetime juggling these ancient roots

while braiding them into the sovereign pathways I came here to forge.

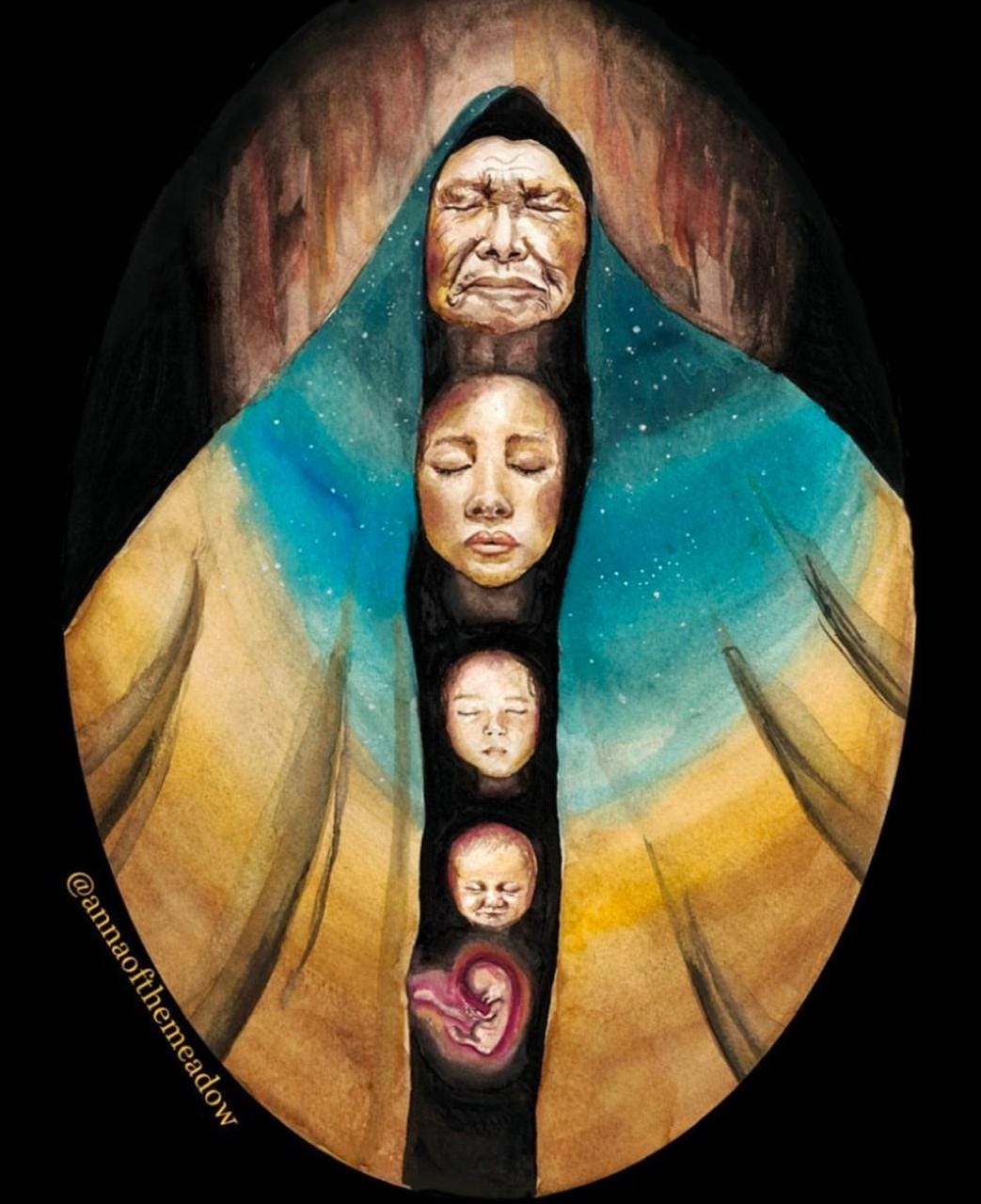

More than a decade after my first solo trip to India, I discovered a fascinating fact: every woman alive today has once lived in the womb of her grandmother.

When a female fetus is in the womb of her mother, she carries with her all the eggs she will ever possess in her lifetime at four months of gestation. Thus, our cellular life truly begins in our grandmother’s womb, where part of us lives for five months inside our mothers. This creates a continuous matrilineal chain that traces back through time, linking our existence to the first mother like the Russian Matryoshka—wooden stacking dolls that nest within one another to infinity. We women have literally lived inside one another since the beginning of time.

With that knowledge, I realized that the depth of my connection to my matrilineal line was more than just my cultural upbringing. I was a link in an unbroken chain of black-skinned women who hail from the red earth of South Indian soil. They all live inside of me like an imprint on the canvas of my soul. I was undoubtedly born with their wounds and blessings, their shame and power. And I, too, live inside of them, like a seed endowed with an ancestral blueprint that is my holy work to decode, honour and set myself free from.

On the equinox of 2023, I became a mother to my first child, a sweet daughter named Aramara born in Mexico.

In those early days of bleary-eyed, sleepless nights, when breastfeeding left my nipples cracked and bleeding, I found myself weeping for my mother and all mothers. I reflected on our resilience and tenderness, our fragility and endurance, and the sacrifices we make for the sake of the tender women we become—transformed in the crucible of mothering in an often cruel world. As I clung to tenuous wisps of energy, emptied of blood and sweat and prayers, I wept thinking of how hard my mom worked to raise me. I wondered how she spent the days alone at home while my dad was at work, how she got supper on the table each night, and how she did it so far from home.

When I look into my daughter’s eyes, wide with wonder at butterflies, her new baby kitten, and the wetness of water, I know that one day I will be like my mother was and her mother before her, calling out to my daughter across the seas, wishing for her to return to the folds of safety in my embrace.

And yet, it is in her that I have found a deep belonging unlike any other.

She was there all along, carried by my ancestors across generations, and finally in my womb before I pushed her out in what my midwife insisted was the longest birth she had ever attended. She is now the guiding light of our lineage, and the newest link in the chain.

Through motherhood, I have discovered that we belong more to the futures we create than the past we come from.

Aramara enjoys dancing to Tamil songs in the forest, she loves my Indian cooking and video calls her grandma regularly. But she equally devours quesadillas, knows how to bat a stick at a piñata and celebrates holidays like the Day of the Dead. I am learning how to weave our multicultural origins into the tapestry of the life I am creating in Mexico while also acquiring parts of a new identity myself.

We always have a choice in what we want to carry from the past and what we want to pass onward. Aramara has so many cultural identities that influence her, languages she will speak, and places she could live. But that is her journey to figure out.

I once wrote in my diary, “Dear Mother, you are the first land I have ever known.” With those words, I wanted to convey the deep sense of belonging from the idea that our first home is not a nation or territory but our mothers' bodies—those who nourished and carried us.

Perhaps if I can do anything to support Aramara’s growth it is to remind her that no matter how far she wanders from home, I will always be her motherland, a place of safety, holy homecoming and eternal belonging.

Questions for Journalling & Reflection

What do you deeply appreciate about the women in your lineage? How can you celebrate them?

Where do you find your deepest sense of belonging?

What patterns or pain would you like to release from your mother’s lineage?

What do you know about the women in your maternal lineage? Write about your mother, grandmother and great-grandmother.

Imagine you are receiving a blessings from your oldest maternal ancestor. What does she say to you?

Bonus Material for Making it This Far

If you’re still here with me, I’d love to tell you more.

This piece of writing you enjoyed today is part of a much larger body of work that I have been collecting in a series of ancestral memoir essays which one day I will publish in a book. I have a working title for the collection which I am not ready to share but I will say the subject of the book centres on my travels through India on my relentless search for a sense of belonging, as told through lusty, nostalgic, honest essays investigating identity, sexuality, cultural shame and ancestral healing.

A few days ago, my 2017 Macbook Pro went black screen on me. I know my data is safe but I can’t access any of it. Fixing the screen is half the price of a new one but I can only get a Mac with a Spanish keyboard as far as I know. So, for now I’m working on my partner’s PC, which feels clunky and with a steep learning curve. So, I had to get pretty crafty to make this newsletter without my computer (like screenshotting pictures on Instagram, cropping them, and sending them to an app on the PC where I could download them and then upload them here, as one example). The cool part of this very inconvenient experience is, not having access to my saved writing made me write fresh stuff! I’m excited about that. But yeesh, I realized I can live without internet no problem, but I can’t live without my computer y’all.

If you enjoy my writing and would like to support me, let’s cozy up in that cafe corner, you buy me a trad cap, and I’ll tell you a story.

Wow! Sooooo much resonates here. My father immigrated from South India, and my mother is of Scottish descent. The last couple of years I have become quite reflective about the experience of being a white passing person of color in Canada. Most of my life I kind of just considered my white. And it was confusing, cause generally speaking white culture made no sense to me lol. Thank you for writing this -such a wonderful read and a great way to start my Sunday.

Wonderful read Yamuna. I know how much your mom missed her family when you guys were growing up. We use to joke about how Canadian she had become with her wearing jeans. I loved it when she would wear her saris so beautiful. 🥰🥰