“Most men today

cannot conceive of a freedom

that does not involve somebody’s slavery.”

W. E. B. Du Bois

The road to Salaga is a long stretch of pot-holed asphalt intersecting the land of red clay, the colour of the mud houses that occasionally dot the hinterlands of Northern Ghana. The sun is fierce and unrelenting, making the wild earth feel inhospitable as it whips through my hair. The people who live here are of formidable character; they are devout and as resilient as the giant baobabs that defy the unforgiving elements. In 2017, I made the 100-kilometre, 2-hour journey to Salaga on the back of a motorcycle from the town of Tamale, where I was visiting my Dagomba boyfriend. That’s a whole other crazy story I’ll tell you one day.

I had no other reason to visit Salaga except that through reading Saidiya Hartman’s book, “Lose Your Mother,” I learnt that this little-visited town in the Eastern Gonja district, was once a bustling trade centre for salt and kola nuts and later became the epicentre of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. As an African American with no relatives in Ghana and searching for her lost origins, Saidiya traces a slaves journey from Salaga to the coast, where the now popular tourist attraction Elmina Castle looms over The Atlantic Ocean, once a gold trading outpost built by the Portuguese in 1492 and later turned into a depot where over ten million enslaved Africans were shipped off to plantations in Portuguese colonies and the Americas.

Although the Portuguese were the first colonial power to engage in the Atlantic Slave Trade, it was deep in the heart of North Ghana, in Salaga, where the largest slave market in West Africa was located. There was little mention of it anywhere except for a signboard in the centre of the local bus station which read, 'Welcome to Salaga Slave Market," erected on the spot where slaves were once brought in chains, oiled in shea butter, and tied to the tree to be sold.

It felt like sweet serendipity when a stranger approached me while photographing the sign. My Dagomba boyfriend conversed with the man in Hausa, a language widely spoken in Nigeria and along West African trade routes. It seemed there was only one person in the entire town who could assist us with investigating the remains of the slave trade, and this stranger was willing to take us right to his doorstep.

Lazing shirtless and chewing on a twig, Ibrahim Iddrisu, known locally as Brazil for being a great footballer in his youth, stood hesitantly in the doorway of his modest home. In perfect English, he explained that he had just got home and was watching TV when we arrived. I sensed that he would have rather been relaxing at the height of the midday sun. Still, he put on a traditional indigo-dyed smock and asked for 5 cedis ($1.50) to fill up the tank of his motorcycle so that he could show us what was left of the origins of slavery in Salaga.

During the short drive to our first stop, he waved at and greeted the people we passed, a clear sign of his notoriety in town. We parked our bikes on a vibrant green patch and followed Brazil through dense foliage along a barely visible footpath that opened to a semi-cleared plot of land. Brazil spoke about the generations that came before him—his grandfather and father—who had taken him as a child through these same fields to witness a history that most others preferred to forget. This experience planted the seed for Brazil to become the most knowledgeable local figure and the unofficial gatekeeper of the largely unknown remnants of slavery in Salaga.

“There were once pits dug as far as the eye could see. It’s all overgrown now, but in those days this land used to be maintained.”

The "pits" that Brazil mentioned were dirt trenches where enslaved individuals were brought to be washed and oiled before being taken to the central market in town. Not far from these earthen holes were a few stone water wells from which water for washing was fetched. Brazil noted that even today, this sweet water was the purest in town and insisted that we taste it. I hesitated at first, but I eventually took a gulp and somehow felt better for having taken a piece of this tragedy into my own body.

As we explored the grounds where thousands, if not millions of captive Africans had passed, I couldn’t understand why Salaga? Brazil explained,

“Salaga is the center of Ghana. There are roads in all directions and slaves were brought here not just from other regions, but from all of the countries which surround us. You see, Salaga was once a major market town in the trade for kola.”

In "Lose Your Mother," Saidiya reflects on how Ghanaians often viewed her as "one of the lucky ones." Instead of being the descendant of a slave or a slaver in Africa, she had made it to America. It’s understandable that they felt this way—life in the remote Northern Region felt worlds apart from modern society and offered little opportunity for advancement. Before we continued on our impromptu tour, Brazil turned to me with a serious expression on his face.

“My sister, you know, it was not only your people which enslaved ours. It was we Africans who started the slave trade and sold our own people to the Europeans.”

As we all stood over the blue pools of well water, Brazil shared how African American tourists often arrive in large numbers, moved to tears at the stone archway before immersing themselves in the water. They come in search of a connection to their roots, only to discover themselves in a place that barely acknowledges its own historical involvement in their loss of identity. I understood why this was so significant. In the Americas, many Africans are likely descendants of victims, but here in Salaga, their ancestors might have been among those who enslaved them.

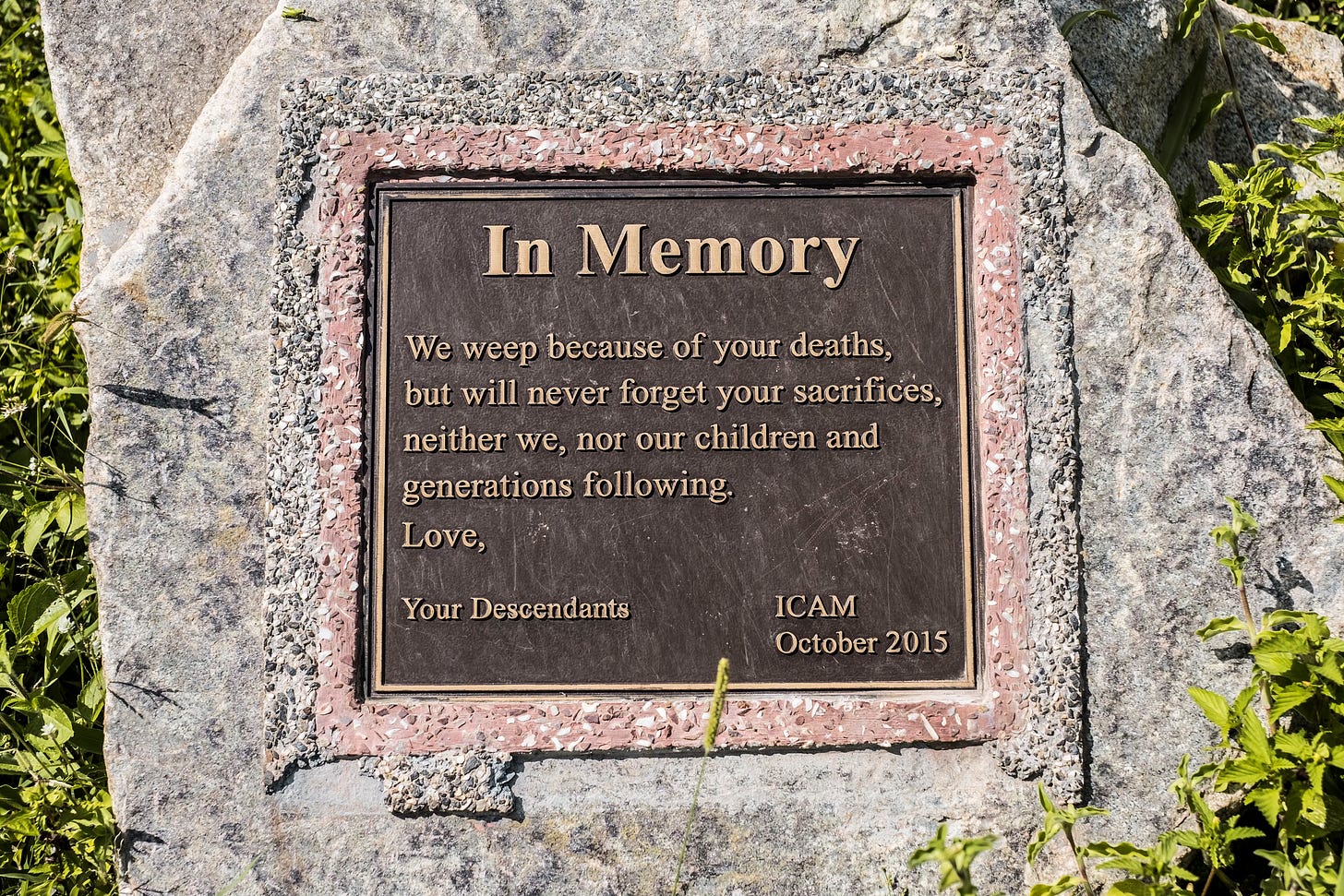

We rode our motorcycles through a cluster of mud houses and giant baobabs until we reached a field. The smell of feces was overwhelming. I carefully stepped ten paces into the patch of green where an African American pastor had erected a stone plaque atop a mass gravesite.

The Salaga Museum was our final stop. Brazil had guided us in a perfect circle, bringing us back to the town center, where a beautiful shaded courtyard was filled with well-dressed men—some gathered to pray, others to gamble. We waited for someone with the keys to arrive and open the museum door, which revealed a disappointing collection of rusty spears, shackles, and calabash gourds that resembled props from a Pirates of the Caribbean movie set. The floor was covered in a thick layer of sand, likely leftover from the previous harmattan season. My Dagomba boyfriend placed his hands inside some hanging cuffs for a photo, creating a strikingly realistic depiction of what we had only imagined. It was at this point that Brazil took his leave. After a few handshakes and a humble tip, we bid him farewell and concluded our journey through the history of the slave trade in Salaga.

Following an unsavory lunch at an adjacent restaurant, I rode back to Tamale with an unsettled feeling in my gut. Slavery in Africa has been one of the darkest stains on our collective consciousness and to this day has resulted in lasting legacies of inequality and injustice for Black people. For something so historically significant, it seemed decidedly unrecognized. There is very little in Salaga and even Ghana to acknowledge the forcible displacement of millions of Africans whose descendents continue to be severed from their roots in societies largely built on the bodies of Black slaves.

I had hoped that visiting Salaga would help me find some sense of justice for this history, but instead, I encountered a place on the margins of civilization, where life was still about survival. As I traced these ancient routes of grief back to where it all began, I felt the weight of history in the air. It carried both the irreplaceable loss of life, culture, and dignity as well as the whispered promise that remembering is its own kind of return.

You're stories never cease to amaze me. :-)

Thank you, Amiga. I'm so glad you are enjoying, much more to come!