In the autumn of 2015, at age thirty-six, I touched down on the damp earth of Ireland on a family vacation with my dad and brother.

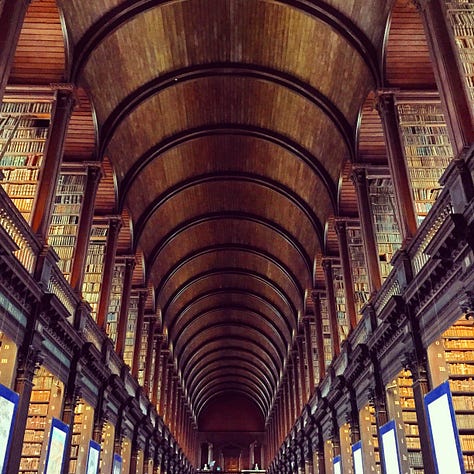

We would spend three weeks tracing the edges of the land—wandering through artist studios and handicraft shops, eating fluffy homemade scones in every roadside bakery we passed, sipping tall pints in noisy pubs and marvelling at the Book of Kells housed in Dublin's Trinity College Library. Most notably, we would try our best to find the very stone house in Connemara where my great-grandfather, Thomas Flaherty, may have been born but was most certainly baptized on the 8th of December, 1875.

My father, Tommy, who received his grandfather's name, had made the trip to Ireland in 1968, sandwiched in a tiny car with his parents and four brothers. His father, Thomas, had won big on the horses that year and could afford to take the family on a weeklong vacation. My father had few memories to recount, but he did mention that his relatives lived in the horse stable, and the animals lived in the house, which was in great disrepair. So, from our hotel room in Galway, we called Aunt Mary in Glasgow--my grandfather's sister--the day before our intended mission. Over a crackling phone line and difficult accent for my unaccustomed ear, she directed us to the small village of Camus Oughter in the mountain pastures and bogs of the Connemara Gaeltacht, an Irish-speaking region of County Galway.

My great-grandfather died the year before my father was born. So, like myself, he was only known through the stories others told. It was said that he was an illiterate Gaelic speaker who swore up and down that he often talked to faeries and leprechauns. Now, any Irishman would tell you that anything is possible with a little drink in you while walking the boglands on a foggy night, but my great-grandfather vowed it to be true till his death.

Unlike this first visit to Ireland, I had visited my father's birthplace in Scotland several times, to the point where I didn't feel connected to my Irish roots. As an unchaperoned seventeen-year-old, I travelled with my little brother to spend the summer with my father's family outside Glasgow. I wore mini skirts and platform boots each weekend to visit the local club, Nightingales, jokingly dubbed "Nightmares," with my elder cousins. Consequently, I spent every late Thursday to Saturday night of my visit clinging to my Aunt Anne's toilet bowl to discharge the excessive amount of rye and coke I had drunk. (I still can’t drink it to this day.) That summer, I made a tally of how many cute Scottish boys I snogged and even kissed my cousin's girlfriend just to show off. But as much as I loved the rolling green hills of Scotland, the castles and Braveheart, no souvenir gift shops sold my last name engraved on a keychain, and I had no tartan to claim as my own. I am a Flaherty with roots to the heathered hills of Connemara. When I returned from that trip, I tattooed my Irish Coat of Arms on my lower back, right on the spot derogatorily regarded as the "tramp stamp," to claim some part of this history and the mysterious forces that had shaped me and I had yet to discover.

According to Aunty Mary's directions, we had to look for a rock with the Irish Gaelic words "Camus Uachtair," which denote the turnoff to miles of hand-built stone walls enclosing properties. Apparently, the entire area was Flaherty territory. As our sleek rental vehicle drove without hurry through the warren of outlined plots, I could sense the curiosity of the locals, who probably assumed we were like so many other North Americans come to look for some long-lost relative we could claim as our own. We mistakenly turned into dead-end roads and backtracked several times until a lady on a walk with two giant sheepdogs pointed us in the right direction. My father suddenly had a flurry of memories and recognized the way, although it had changed significantly since his childhood visit.

At the top of the hill, we pulled into the driveway of an old house where two brothers lived. Joyce was one of the two standing outside in knee-high rain boots, with thick, bushy eyebrows, and wearing an old jumper in tatters. He was a local who had grown up and never left the house next to ours. We piled out of the car and introduced ourselves; I immediately felt how far apart our worlds were, though my father apparently looked like a doppelganger who had once lived nearby. I could barely understand Joyce's thick hinterland accent, but I understood how he represented what my great-grandfather must've been like. He was a man carved from the land itself—humble, weathered, and with such kindness he was practically willing to lie on the ground so I didn't have to step in a puddle. He remembered my family, even though my father had visited when Joyce was five years old.

I stood at the perimeter of a crumbling stone edifice, wind-whipped and wide-eyed, feeling the pull of something deep and wordless—a belonging older than memory.

The land unfolded before me in a hush of green and stone, the low hum of the wind weaving through the hills. A barely visible path led to the crumbling ruins of a cottage, its roof caved in like a mouth mid-sentence, waiting for me to listen. I reached out, tracing my fingers along the cool, weathered stone, wondering if my great-grandfather's hands had once done the same.

We all took a moment to walk the land, shooting photos and videos of the stone that had once shielded my family from the bitter Connemara winds. I felt embarrassed that we were acting like tourists in Joyce's life but he didn't seem bothered. He stood to one side, watching with curiosity and equal timidness to be caught interested in our presence. Somewhere beneath me, buried in the layers of earth and time, were the footsteps of those who had come before—farmers, poets, wanderers, and weavers—bloodlines tangled like roots in the dark soil. Everything was overgrown with tall grasses. As a young man, I imagined Thomas seeking a better life when he set off from this place, walking across the rolling green fields, following the labyrinthine walls through a hundred different kinds of rain and across the sea, which would deliver him to new possibilities. He would eventually serve in the 8th Royal Sussex Pioneers during the First World War and marry Annie Church in St Mary's Chapel in Glasgow. They would have three children, Mary, Ellen, and my grandfather, Thomas. With that singular migration, my patrilineal bloodline would become hyphenated. We became Irish-Scots.

Though little was left of our history, finding this out-of-the-way place where my people once lived was like collecting another piece of my personal story. Though truthfully, I come from many places. Born in Canada to a Tamil woman and a Scottish father, with Irish curls and Indian hips, my legs straddle disparate lands, rooted in contradiction, ever reaching toward wholeness. This fascinating friction between warrior Robert the Bruce and Tamil film hero Rajinikanth is like the axis of my existence. These cultural crossroads are my daily compass and my quiet storm, the restlessness I carry in my marrow. For this reason, I've long been consumed by the act of "re-membering" my quartered existence. Like limbs stretched in opposing directions or people severed from their traditional lands, my ancestral pilgrimages are my way of reclaiming lost soul territory.

On my journey to Ireland, I discovered that, like my kinfolk, I am a child of lament, literature, and rebellion.

This primordial land of rust, iron, and bone whispers in the old tongue: the secrets of the Druids, tales of the faeries, and the mysteries of the Celts. It is where locals wrap themselves in a warm blanket of folklore. Here, one can find window sills decorated with flowers and trinkets for the passerby's pleasure, bringing life to a place often painted in fifty shades of grey. It is where I finally found keychains with my surname engraved, a castle where my fierce ancestors once ruled, and our Irish Gaelic clan name, Ua Flaitbeartaig, hanging above a pub door. One of the most memorable finds on our trip was meeting the eccentric musician Mazz O'Flaherty, the infamous owner of Dingle's smallest record shop. She was emblematic of the jovial nature of the Irish and legitimately looked like one of my kin.

Like every person visiting that island jewel in the North Atlantic, I wanted to stay in Ireland forever. It is a place where I imagined myself writing a book while listening to the patter of raindrops on the windowpane. I like to think that some part of me will always be there, just as my great-grandfather's adventurous spirit indeed resides in me. Without a doubt, I am a result of the choices he made in his life, and this simple fact urges me to contemplate which roads I will take in mine.

On the final days of our trip, we visited The Famine Memorial in the Dublin City Docklands, a haunting tribute to the Great Starvation of the 19th century. The life-size bronze figures — gaunt, barefoot, draped in sorrow — seemed to stagger forward not just with hunger, but with the weight of departure. I stood in silence, watching these frozen echoes of those who had no choice but to leave, their exodus scattering seeds across the world.

This mass migration didn’t just disperse a people; it fractured identities, reshaped nations, and echoed through generations. I am one such echo. My Irish ancestry is not exceptional, but it binds me to a global lineage of dislocation, to the sorrow and strength of those who left and those who stayed. In an age when migration is too often met with suspicion and fear, standing there, I was reminded that so many of us are here because someone once had to leave. My identity, like the memorial itself, is forged at the crossroads of longing, survival, and reinvention.

Although my story spans continents as a child of many migrations, some part of me will always be a Connemara girl.

Writing Prompts for Re-membering

What land calls to you — whether or not you've ever been there? Let the soil, weather, and history speak through your body as you write.

Where does your last name take you? What stories, meanings, or myths does it carry?

Write about the friction and the beauty of being from many places. Where do the seams of your identity tug or tangle?

What were the choices your ancestors made that brought you here? Write about one of those turning points and how it echoes in your own life.

Describe your personal geography of belonging, not a map, but a sensory landscape made of all the places that hold you.